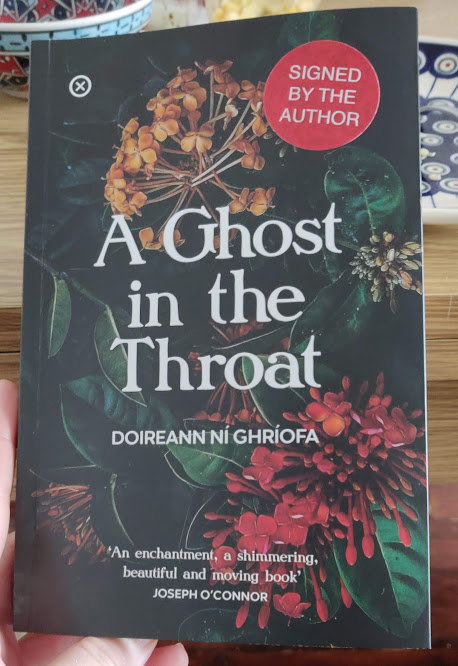

In a short space of time, Tramp Press established itself as a publisher of books that capture the modern Irish experience. Over the last few years, its publication of both fiction and non fiction, such as Solar Bones, Notes to Self, and Handiwork, has raised the bar so high that I’ll gamble on reading anything Tramp Press puts out regardless of subject. For me, reading, A Ghost In The Throat was one of these gambles. If A Ghost In The Throat had not been published by Tramp Press, I’m not sure I would have read it.

Without knowing the first thing about Doireann Ní Ghríofa, the subject of this book would have been enough to dissuade me from reading it. Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, whose keening I was unfamiliar with, lived in a period of Irish history that I find unbearable to read about. I struggle to read accounts of both early Irish civilisation and Ireland under British rule. I have vivid memories of the despair I felt sitting in the library pouring over a battered copy of Maire and Liam de Paor’s Early Christian Ireland among other books that were prescribed reading in first year of university. I avoid reading books about early Ireland because it saddens me to read of a culture that didn’t survive. I avoid reading books about Ireland under British rule because I don’t enjoy reading the mechanics of how the culture didn’t survive. Ní Ghríofa’s work explores the life of Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, whose husband Airt Uí Laoghaire was gunned down by British soldiers in 1773 in rural Cork. The historical timeline, setting, and backdrop are all laced with a politics that I avoid in my leisurely reading. However, Ní Ghríofa has managed to deliver a text so maternal that it shields the reader from the politics of the era. She has wrapped her words in a warmth that is uniquely feminine. At the beginning of the book, Ní Ghríofa asserts that this is a female text, and she does not exaggerate. This is a female text that is swimming with the deranged and milk-drunk optimism of mothers who continue their daily tasks regardless of the era and crises that erupt in the outer world.

Some people whether real, fictional, or historical, stay with us for a lifetime. Regardless of whether we knew them or ever met them, we encounter them and elevate them to an eternal pedestal. There’s a window of time in which this is more likely to happen. As children, with one foot still in the dreamworld, we’re too removed to form this kind of connection. As adults, we’re too busy or broken, too cynical or distracted. During those tender years between childhood and adulthood, in a haze of hormones, we run a high risk of imprinting upon someone and carrying them around in our heads for the rest of our lives. Ní Ghríofa encounters Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill at three stages of her life. As a child, her first reading of Ní Chonaill’s Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire fails to leave a dent. As a teenager, she identifies with the pain of lost love in the way only teenagers can. As an adult, forced to leave Cork city as the rental crisis made life there unsustainable for her and her young family, Ní Ghríofa drove through the unfamiliar countryside that was now her home and realised she was living close to where Ní Chonaill spent her married life. Somewhere between her third and fourth child, between the school runs and the household tasks, Ní Ghríofa found herself compelled to attempt a narrative of the life of Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill. She found herself haunted by and haunting Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill. In trying to shed light on the life of a female poet in 18th century Ireland, Ní Ghríofa sheds light on the life of a female poet in 21st century Ireland. In painting a portrait of the life of Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, Ní Ghríofa paints a portrait of herself.

A Ghost in the Throat is a series of parallels, of cycles, of paying it forward in words, deeds, breast milk, and pony tails. While Ní Ghríofa searches for Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, we travel with her between Muskerry and Derrynane, between her and Ní Chonaill’s own rebellions and lust.

The lives and deeds of Irish women are as poorly recorded and appreciated as any. Although Ní Ghríofa leaves no stone unturned in her pursuit of Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, we only have of Ní Chonaill what Ní Chonaill willingly gave. Very little else remains of her: no artefacts or accounts of her life outside of her keening. While she searches for Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, Ní Ghríofa cherry-picks intimate moments from her life that reveal her own sexuality, sorrow, lust for life, and a maternal instinct that threatens to envelop everyone in its path. This account of her own life is probably the account she would have loved to read about Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill. Despite the fact that we now live in the year 2020, the revealing nature of A Ghost In The Throat is still a brave act. In a country with a small population, often with one or two degrees of separation between people, texts this intimate are few and far between.

If I hadn’t read this book, I would have missed out. Ní Ghríofa created a work so powerful that I can imagine some future youth, tender in age, imprinting onto Ní Ghríofa, elevating her to a pedestal, and in mining Ní Ghríofa’s life, discovering herself.